What We Talk About When We Talk About the Climate

From the Editor

-

-

Share

-

Share via Twitter -

Share via Facebook -

Share via Email

-

Before I came on as editor of the Breakthrough Journal, I spent years in foreign policy journalism. From that perch, covering the climate always presented a challenge. It was clear that it was important to do, but how to do so both responsibly and in a way that would attract eyeballs was less straightforward.

The stories that did the best were routinely the ones that flouted my sense of best practices. They catastrophized, they decontextualized, they treated climate change as sui generis, divorced from the big international relations concepts—sovereignty, realpolitik, self-interest—that were more rigorously applied to other topics in global affairs.

In turn, climate became less a subject to examine through existing frameworks and more a framework into which every other topic might be jammed. Coverage looked to the implications of global warming for conflict, democracy, development, international cooperation, and the like, rather than what geopolitics, for example, might mean for dealing with the climate.

I think that’s unhelpful—or at the very least, inadequate. And I hope the pieces collected in this issue offer a corrective. From security, to development, to human rights, and beyond, they each show how a big issue in geopolitics came to be wrapped in a climate coating, why that’s harmful to international progress and the climate, and what a more serious approach to both might look like.

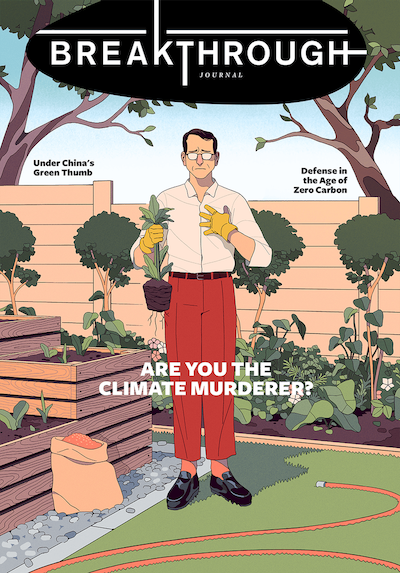

Breakthrough executive director Ted Nordhaus opens the issue with “Am I the Mass Murderer?,” a searing look at efforts to discredit all but the most apocalyptic visions of the planet’s future. It is far better, he urges, to understand the possible consequences of climate change as a race between two trends: The planet is warming, yes, but greater societal wealth is also increasing our resilience against the very changes warming will bring. The choice, he concludes, is not between survival and extinction, but “rather between marginally better and worse futures—futures that will be shaped by a kaleidoscope of forces, most of them having not so much to do with climate change.”

In a follow-on essay, “The Dogma of Degrees,” M.S. Swaminathan Research Foundation’s T. Jayaraman expands on the role of uncertainty in addressing climate change. It is “the place from which possibilities emerge,” he writes, an idea that also has “a long history in democratic politics.” To become dogmatic is to put unnecessary limits on global climate efforts while also striking a blow to democracy worldwide.

The point that much of our climate discourse has little to do with the climate underpins many of the other articles collected for this issue as well. In “The Guns of Warming,” Berggruen Institute’s Nils Gilman explores the genesis of the idea that climate change will have serious national security implications—an effort, he writes, led by security analysts looking to get the government to take warming seriously. “As time has gone by,” though, “that strategy has become more and more dubious.” Rather than “motivating a Great War on Climate Change,” he argues, “the defense establishment’s focus on climate-related security challenges has instead served as little more than justification for enriching the military-industrial complex” in support of the same old goals it always had.

Meanwhile, climate goals have also found their way into global development lending, where Breakthrough’s Vijaya Ramachandran and University of Chicago’s Arthur Baker find that the World Bank and others are increasingly bowing to pressure to ban loans to the least developed countries for fossil fuels. That makes little sense, though, as either a development strategy or a way to combat climate change, they write in “Let Them Eat Carbon.” “Pressuring low- and lower-middle-income countries to replace plans for gas power with solar or wind energy will have limited climate benefits,” since “those countries’ emissions are drops in the bucket.” Meanwhile, “reducing poverty is not feasible without access to cheap and reliable energy,” and that energy won’t come without investment in existing energy infrastructure.

To put an even finer point on how contorted much of the climate discourse has become, look to China. In “Beijing’s Green Fist,” Human Rights Watch’s Yaiqu Wang notes that because of the scale of Chinese emissions, many are desperate for China’s cooperation and have applauded its bold commitments to reach carbon neutrality by 2060. Before people “get giddy about working with Chinese authorities on climate change,” Wang warns, “they should have a better understanding of the work Chinese authorities actually intend to do, and the human rights abuses built into it.” From recording devices in trash can lids to forced labor in Xinjiang, “it is increasingly clear that the Chinese government has been exploiting environmental causes to consolidate political control and expand its power at the expense of human rights.”

For writer Fred Pearce, the problem goes beyond defense, development, human rights, and conflict to the future of the population itself. Ehrlich’s population bomb, where the number of people would outstrip the earth’s ability to provide for them, has long been diffused, first by technological innovations that allowed the world to produce more from less and now by falling birth rates around the world. That might seem like a cause for celebration among environmentalists, but, not so fast, he cautions in “The Dangers of Implosion.” “Inasmuch as stark populations declines could eventually lead to de-densification, a weaker workforce, slower economic growth, and innovation, it may also represent a challenge” to the kind of development the world will need to deal with the climate problems already baked into our future.

One such development, Krystle Wittevrongel from the Montreal Economic Institute argues in “Emissions in Reverse,” is CCUS technology. Without it, she writes, the world will not be able to get to net zero. Yet some countries, like the United States, are poised to benefit more than others—especially when it comes to the “use” and “storage” parts of CCUS—and that will come with its own challenges. That leads us, in a final piece, to the need for industrial policy. “The terms ‘climate-friendly’ and ‘industrial policy’ may seem at odds,” University of Calgary’s Sara Hastings-Simon writes in “We Need an Industrial Policy for the Climate.” “‘Climate-friendly’ feels younger, in vogue, suggesting flashy startups promising to lead the way with fancy new tech. ‘Industrial policy’ evokes the cranking gears of some manufacturing heyday, complete with older gentlemen planning the future for everyone.” Yet the two are natural partners, since any effort to get to carbon neutral will have to overcome industrial inertia. “And that’s exactly the type of challenge that industrial policy is well suited to address.”

The essays collected in this magazine don’t shy away from complicating discussions around the climate. And they shouldn’t. When we talk about climate change, we aren’t talking about a unified theory for the world’s future. Rather, we are talking about many other forces and frameworks—geopolitics, economics, geology, development, governance, and more—and how they intersect with each other and the world around us.